LEARNING LOG FOR POSTGRADUATE 2013 BY ANSHLEY

This is an individual Learning Log for PGO1- RESEARCH PROCESS which will used in conjunction with other postgraduate units (PG02, PG03, PG04 & PG05).

This is an individual Learning Log for PGO1- RESEARCH PROCESS which will used in conjunction with other postgraduate units (PG02, PG03, PG04 & PG05).

Behind The Scenes Footage of The Hobbit 3D

|

| The space of 3d cinema. A cone with its vertex at your eyes, extending to 50 feet away. The screen, S, is 20 feet or more away. P is positive parallax space. N is negative parallax space |

|---|

Sony Professional’s Paul Cameron on filming in 3D.

In the two weeks since it launched, Gravity, the sci-fi spectacular starring Sandra Bullock and George Clooney, has made $191m (£119m) at the box office.

But it’s not just the size of the receipts that has surprised movie experts – it’s the fact that 80 per cent of the audience are prepared to pay a premium of between $3 and $5 to watch the film in 3D. To put that in context, it is a higher proportion than for Life of Pi or even Avatar, the film that broke all box office records in 2009 and was supposed to herald the coming of 3D as a mass-market phenomenon.

Indeed, before Gravity’s eye-popping numbers were revealed, many critics had been talking about the death of 3D. For Ryan Gilbey of the New Statesman, the technology has a fundamental problem it can never overcome – the need to wear glasses. “3D puts a barrier between us and the screen. You need to be immersed in a film to truly enjoy it and all of a sudden you have equipment that prevents that,” he said.

But a rival technology has emerged that could change all that. The X, the first film to use Screen X technology, was unveiled last week at the Busan International Film Festival in South Korea. Screen X presents viewers with a 270-degree field of vision that creates an immersive experience without the need to wear 3D glasses. It even solves the widescreen problem that has hindered the format since 3D first appeared in 1915.

The “golden era” for 3D took place between 1952 and 1954, reaching a peak with Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial M For Murder. Although the film was a success in 3D, the director himself admitted afterwards that he believed 3D to be a “nine-day wonder – and I came in on the ninth day”. At the time both exhibitors and audiences were uncomfortable with 3D, preferring instead to try out widescreen formats such as Cinemascope and Cinerama.

Widescreen has had a habit of killing off 3D. In the early 1980s there was another wave of 3D headed by Jaws 3D and Amityville 3D. Yet the production costs were high and audiences were unconvinced by the plastic glasses that had one red lens and one green.

The format remained niche even with the introduction of IMAX, as the cost of building new cinemas to support the technology has always been prohibitive.

The holy grail has been to design a format that is both widescreen and immerses the viewer in the film without the need for special glasses nor for completely new auditoriums.

This year’s Gravity

Enter Screen X. The South Korean company behind the technology, CJ CGV Screen X, began development work in January 2012. CJ Entertainment is South Korea’s most prominent producer and distributor of films, and runs the CGV chain of cinemas. Screen X has been implemented at 23 theatres in Seoul on 47 screens, where audiences have already had a taste of the technology through advertisements running before films.

By DAVID LIEBERMAN

B. Riley & Co analyst Eric Wold favors the second part of the equation, but says consumer pushback may also account for the disappointing 3D ticket sales that just led him to downgrade tech company RealD to “neutral” from “buy.” That contributed to a 6.2% drop in the company’s share price in early trading.

Wold notes that 3D accounted for 31% of thedomestic box office for Disney/Pixar’s Monsters University this weekend, making it “the lowest of any animated title in history” behind Brave‘s 34%. And Paramount’s World War Z, with 34% of box office from 3D, was “the lowest of any action movie in history” after Paramount’s Captain America with 40%. These aren’t blips: The 3D domestic attach rates (the percent of total box office) “have been stabilizing in the 30%-45% rate — which, unfortunately, has become a trend” with all movie genres, Wold says. Consumers may be fed up paying an extra few bucks for 3D, although Wold notes that “we are not seeing this with IMAX screens.”

More likely, he says, is that theaters don’t have enough venues that can take advantage of the growing number of 3D films that studios are cranking out. This year we’ll see 17 major 3D films between the beginning of March and the end of July, up from eight in the same period in 2010. But theaters have cut way back on their orders for the technology to show 3D films, satisfied to have anywhere from 35% to 50% of their screens capable of handling the format. For example, RealD outfitted 1,800 screens in the first three months of 2011 but just 200 in the same period this year. That’s why Wold says he remains optimistic about long-term prospects for RealD, despite his retreat today on the stock. Based on the strong overall box office sales, “we would not be surprised if domestic exhibitors are hitting a point again where more 3D-capable screens are needed.”

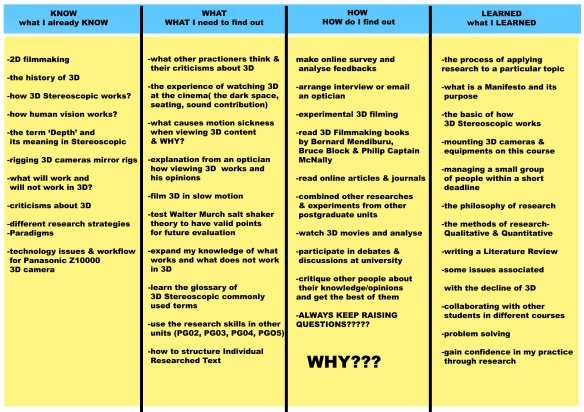

First of all, my area of practice is 3D Stereoscopic Media (3DS) and I did not choose my practice because there is a lack of skillset in that department or to get a well-paid salaried job as my priority. The main reason why I have chosen this field is purely due to fascination and passion which I experienced in my childhood and I came across again during my BA(Hons). Therefore, I decided to explore how 3DS works so that I can amazed other people with this incredible experience. When I started the course in September, things began to change where I found out 3DS in serious decline and came across very strong criticisms by the general audience and filmmakers.(see Fig1)

Fig1.

Many people disliked it and were very opinionated by the negative aspects of this incredible optical illusion. As a result, I am going to do my research of what is causing people to hate 3D, analyse critics, learn good techniques. To tackle these issues it is very important for me to explore bad 3D by either correcting them or avoiding them in order to deliver excellent 3D experience to the audience.

To begin with, one of the most respected film editor and sound designer Walter Murch has strong criticisms about 3D in the film industry. To begin with, Murch opinions about 3D are that it very dark and lack brightness compared to 2D movies. This is because we have to wear the special passive glasses to view 3D content at the cinema. Moreover, scaling is an issue which can make the audience feel disconnected from the scene because the illusion would be impossible in real life. Furthermore, he uses the salt shaker test to explain the way natural vision works mainly explaining converging and focussing. Murch argues that 3D in movies and our brains are not a good combination and it will never work.

Murch correctly explains that, when the brain is presented with the stereo pairs (image from each eye), it adjust its parallax/convergence and focus the subject. But Murch argument about how focussing works is not strong enough in his letter. He states that the brain automatically focus to a shorter distance when the interocular angle decreases and this differ from how focus takes place on viewing stereoscopic content. However, the brain’s calculation for interocular angle and focusing is not the same, as the brain focusing mechanism is mainly established by edge detection. If we stare at an object for a long time, our brains keep adjusting by focussing around the object, making minor adjustments to make sure it is right in focus.

I do agree with Murch that lack of brightness and scaling have existed in every 3D movies so far but the darkness issue can be solved in the future with new technologies and research. We have to take into consideration that the first stereoscopic feature was made in 1952, The Bwana Devil, and since then it has been improving with pioneering technology from James Cameron with Avatar. Therefore, I do not agree with Murch that 3D will never work. 3D works the opposite of 2D movies and the root of the problem is that most of the 3D movies made, are shot using 2D techniques. The reason why directors chose to do so is because a movie should originally in 3D will eventually have a 2D version extracted by showing only one eye. Therefore, the distributors urge film producers and directors to film 2D techniques because the majority of money comes from 2D shows and sales. What happens in this case, it becomes a money generating project rather than offering 3D experience and immersion to the audience. Therefore, our eyes try to view things the way we are not used to, thus forcing our brain and vision to function which eventually leads to headaches, migraines and sickness. These are caused by fast changing scenes per second and big depth difference between shots.

It has been tried and tested in Avatar that POV(point of view) scenes works appropriately which gives the audience the experience of being part of then screenplay or watching a live theatre with actors. Also, In Avatar, the convergence points throughout the movie was at the subject and that is why it worked well.

by Roger Ebert

I received a letter that ends, as far as I am concerned, the discussion about 3D. It doesn’t work with our brains and it never will.

The notion that we are asked to pay a premium to witness an inferior and inherently brain-confusing image is outrageous. The case is closed.

This letter is from Walter Murch, seen at left, the most respected film editor and sound designer in the modern cinema. As a editor, he must be intimately expert with how an image interacts with the audience’s eyes. He won an Academy Award in 1979 for his work on “Apocalypse Now,” whose sound was a crucial aspect of its effect.

Wikipedia writes: “Murch is widely acknowledged as the person who coined the term Sound Designer, and along with colleagues developed the current standard film sound format, the 5.1 channel array, helping to elevate the art and impact of film sound to a new level. “Apocalypse Now” was the first multi-channel film to be mixed using a computerized mixing board.” He won two more Oscars for the editing and sound mixing of “The English Patient.”

“He is perhaps the only film editor in history,” the Wikipedia entry observes, “to have received Academy nominations for films edited on four different systems:

• “Julia” (1977) using upright Moviola • “Apocalypse Now” (1979), “Ghost” (1990), and “The Godfather, Part III” (1990) using KEM flatbed • “The English Patient” (1996) using Avid. • “Cold Mountain” (2003) using Final Cut Pro on an off-the shelf PowerMac G4.

Now read what Walter Murch says about 3D:

Hello Roger,

I read your review of “The Green Hornet” and though I haven’t seen the film, I agree with your comments about 3D.

The 3D image is dark, as you mentioned (about a camera stop darker) and small. Somehow the glasses “gather in” the image — even on a huge Imax screen — and make it seem half the scope of the same image when looked at without the glasses.

I edited one 3D film back in the 1980’s — “Captain Eo” — and also noticed that horizontal movement will strobe much sooner in 3D than it does in 2D. This was true then, and it is still true now. It has something to do with the amount of brain power dedicated to studying the edges of things. The more conscious we are of edges, the earlier strobing kicks in.

The biggest problem with 3D, though, is the “convergence/focus” issue. A couple of the other issues — darkness and “smallness” — are at least theoretically solvable. But the deeper problem is that the audience must focus their eyes at the plane of the screen — say it is 80 feet away. This is constant no matter what.

But their eyes must converge at perhaps 10 feet away, then 60 feet, then 120 feet, and so on, depending on what the illusion is. So 3D films require us to focus at one distance and converge at another. And 600 million years of evolution has never presented this problem before. All living things with eyes have always focussed and converged at the same point.

If we look at the salt shaker on the table, close to us, we focus at six feet and our eyeballs converge (tilt in) at six feet. Imagine the base of a triangle between your eyes and the apex of the triangle resting on the thing you are looking at. But then look out the window and you focus at sixty feet and converge also at sixty feet. That imaginary triangle has now “opened up” so that your lines of sight are almost — almost — parallel to each other.

We can do this. 3D films would not work if we couldn’t. But it is like tapping your head and rubbing your stomach at the same time, difficult. So the “CPU” of our perceptual brain has to work extra hard, which is why after 20 minutes or so many people get headaches. They are doing something that 600 million years of evolution never prepared them for. This is a deep problem, which no amount of technical tweaking can fix. Nothing will fix it short of producing true “holographic” images.

Consequently, the editing of 3D films cannot be as rapid as for 2D films, because of this shifting of convergence: it takes a number of milliseconds for the brain/eye to “get” what the space of each shot is and adjust.

And lastly, the question of immersion. 3D films remind the audience that they are in a certain “perspective” relationship to the image. It is almost a Brechtian trick. Whereas if the film story has really gripped an audience they are “in” the picture in a kind of dreamlike “spaceless” space. So a good story will give you more dimensionality than you can ever cope with.

So: dark, small, stroby, headache inducing, alienating. And expensive. The question is: how long will it take people to realize and get fed up?

All best wishes,

Walter Murch.